Are Amoeba Plant Like or Animal Like

Are Amoeba Plant Like or Animal Like

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; plural am(o)ebas or am(o)ebae ), [i] oft called an amoeboid, is a blazon of prison cell or unicellular organism which has the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and retracting pseudopods. [2] Amoebae do not grade a single taxonomic group; instead, they are found in every major lineage of eukaryotic organisms. Amoeboid cells occur non only amongst the protozoa, but also in fungi, algae, and animals. [three] [4] [five] [vi] [7]

Microbiologists often use the terms "amoeboid" and "amoeba" interchangeably for any organism that exhibits amoeboid movement. [viii] [ix]

In older nomenclature systems, most amoebae were placed in the course or subphylum Sarcodina, a group of unmarried-celled organisms that possess pseudopods or move by protoplasmic flow. Yet, molecular phylogenetic studies have shown that Sarcodina is not a monophyletic group whose members share common descent. Consequently, amoeboid organisms are no longer classified together in one group. [10]

The best known amoeboid protists are Anarchy carolinense and Amoeba proteus , both of which take been widely cultivated and studied in classrooms and laboratories. [11] [12] Other well known species include the and then-called "brain-eating amoeba" Naegleria fowleri , the abdominal parasite Entamoeba histolytica , which causes amoebic dysentery, and the multicellular "social amoeba" or slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum .

Shape, movement and nutrition [ edit ]

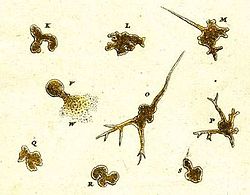

The forms of pseudopodia, from left: polypodial and lobose; monopodial and lobose; filose; conical; reticulose; tapering actinopods; not-tapering actinopods

Amoebae do not have cell walls, which allows for complimentary movement. Amoebae move and feed by using pseudopods, which are bulges of cytoplasm formed past the coordinated action of actin microfilaments pushing out the plasma membrane that surrounds the jail cell. [thirteen] The appearance and internal structure of pseudopods are used to distinguish groups of amoebae from one another. Amoebozoan species, such equally those in the genus Amoeba , typically take bulbous (lobose) pseudopods, rounded at the ends and roughly tubular in cross-section. Cercozoan amoeboids, such as Euglypha and Gromia , take slender, thread-like (filose) pseudopods. Foraminifera emit fine, branching pseudopods that merge with i another to grade net-like (reticulose) structures. Some groups, such as the Radiolaria and Heliozoa, take strong, needle-similar, radiating axopodia (actinopoda) supported from within by bundles of microtubules. [3] [14]

Gratis-living amoebae may exist "testate" (enclosed inside a hard shell), or "naked" (also known equally gymnamoebae, lacking any hard covering). The shells of testate amoebae may be composed of various substances, including calcium, silica, chitin, or agglutinations of constitute materials like small grains of sand and the frustules of diatoms. [15]

To regulate osmotic force per unit area, most freshwater amoebae have a contractile vacuole which expels excess h2o from the cell. [xvi] This organelle is necessary considering freshwater has a lower concentration of solutes (such as common salt) than the amoeba's own internal fluids (cytosol). Because the surrounding water is hypotonic with respect to the contents of the jail cell, water is transferred across the amoeba's cell membrane by osmosis. Without a contractile vacuole, the cell would fill up with excess water and, eventually, burst. Marine amoebae exercise not usually possess a contractile vacuole because the concentration of solutes within the jail cell are in rest with the tonicity of the surrounding water. [17]

Diet [ edit ]

The food sources of amoebae vary. Some amoebae are predatory and live by consuming bacteria and other protists. Some are detritivores and eat dead organic textile.

Amoebae typically ingest their food by phagocytosis, extending pseudopods to encircle and engulf live prey or particles of scavenged material. Amoeboid cells do not take a oral fissure or cytostome, and there is no fixed place on the jail cell at which phagocytosis unremarkably occurs. [eighteen]

Some amoebae also feed by pinocytosis, imbibing dissolved nutrients through vesicles formed inside the cell membrane. [19]

Size range [ edit ]

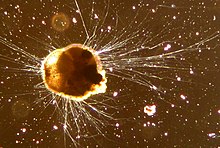

Foraminifera have reticulose (cyberspace-like) pseudopods, and many species are visible with the naked eye

The size of amoeboid cells and species is extremely variable. The marine amoeboid Massisteria voersi is just two.3 to 3 micrometres in diameter, [twenty] within the size range of many bacteria. [21] At the other extreme, the shells of deep-ocean xenophyophores can attain 20 cm in diameter. [22] Near of the costless-living freshwater amoebae commonly found in pond water, ditches, and lakes are microscopic, but some species, such equally the so-chosen "giant amoebae" Pelomyxa palustris and Anarchy carolinense , tin can exist large enough to come across with the naked eye.

| Species or jail cell type | Size in micrometers |

|---|---|

| Massisteria voersi [20] | ii.iii–3 |

| Naegleria fowleri [23] | 8–15 |

| Neutrophil (white blood cell) [24] | 12–15 |

| Acanthamoeba [25] | 12–40 |

| Entamoeba histolytica [26] | 15–60 |

| Arcella vulgaris [27] | 30–152 |

| Amoeba proteus [28] | 220–760 |

| Chaos carolinense [29] | 700–2000 |

| Pelomyxa palustris [30] | upwards to 5000 |

| Syringammina fragilissima [22] | upwards to 200000 |

Amoebae every bit specialized cells and life cycle stages [ edit ]

Neutrophil (white blood jail cell) engulfing anthrax bacteria

Some multicellular organisms have amoeboid cells only in certain phases of life, or use amoeboid movements for specialized functions. In the immune arrangement of humans and other animals, amoeboid white blood cells pursue invading organisms, such as bacteria and pathogenic protists, and engulf them past phagocytosis. [31]

Amoeboid stages besides occur in the multicellular fungus-like protists, the so-called slime moulds. Both the plasmodial slime moulds, currently classified in the class Myxogastria, and the cellular slime moulds of the groups Acrasida and Dictyosteliida, live as amoebae during their feeding phase. The amoeboid cells of the onetime combine to form a behemothic multinucleate organism, [32] while the cells of the latter alive separately until food runs out, at which fourth dimension the amoebae aggregate to course a multicellular migrating "slug" which functions every bit a single organism. [8]

Other organisms may also nowadays amoeboid cells during sure life-bike stages, eastward.g., the gametes of some greenish algae (Zygnematophyceae) [33] and pennate diatoms, [34] the spores (or dispersal phases) of some Mesomycetozoea, [35] [36] and the sporoplasm stage of Myxozoa and of Ascetosporea. [37]

Amoebae as organisms [ edit ]

Early history and origins of Sarcodina [ edit ]

The earliest record of an amoeboid organism was produced in 1755 by August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof, who named his discovery "Der Kleine Proteus" ("the Piffling Proteus"). [38] Rösel'southward illustrations testify an unidentifiable freshwater amoeba, like in advent to the common species now known as Amoeba proteus. [39] The term "Proteus animalcule" remained in use throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as an informal proper name for any large, free-living amoeboid. [forty]

In 1822, the genus Amiba (from the Greek ἀμοιβή amoibe, meaning "change") was erected by the French naturalist Bory de Saint-Vincent. [41] [42] Bory's contemporary, C. G. Ehrenberg, adopted the genus in his own classification of microscopic creatures, simply changed the spelling to Amoeba. [43]

In 1841, Félix Dujardin coined the term "sarcode" (from Greek σάρξ sarx, "flesh," and εἶδος eidos, "form") for the "thick, glutinous, homogenous substance" which fills protozoan cell bodies. [44] Although the term originally referred to the protoplasm of any protozoan, information technology soon came to be used in a restricted sense to designate the gelatinous contents of amoeboid cells. [10] Thirty years after, the Austrian zoologist Ludwig Karl Schmarda used "sarcode" equally the conceptual basis for his division Sarcodea, a phylum-level group made up of "unstable, changeable" organisms with bodies largely composed of "sarcode". [45] Subsequently workers, including the influential taxonomist Otto Bütschli, emended this group to create the grade Sarcodina, [46] a taxon that remained in wide utilize throughout almost of the 20th century.

Within the traditional Sarcodina, amoebae were generally divided into morphological categories, on the basis of the form and construction of their pseudopods. Amoebae with pseudopods supported past regular arrays of microtubules (such as the freshwater Heliozoa and marine Radiolaria) were classified as Actinopoda; whereas those with unsupported pseudopods were classified every bit Rhizopoda. [47] The Rhizopods were further subdivided into lobose, filose, and reticulose amoebae, co-ordinate to the morphology of their pseudopods.

Dismantling of Sarcodina [ edit ]

In the terminal decade of the 20th century, a series of molecular phylogenetic analyses confirmed that Sarcodina was not a monophyletic group. In view of these findings, the old scheme was abandoned and the amoebae of Sarcodina were dispersed amid many other loftier-level taxonomic groups. Today, the majority of traditional sarcodines are placed in 2 eukaryote supergroups: Amoebozoa and Rhizaria. The rest have been distributed among the excavates, opisthokonts, and stramenopiles. Some, similar the Centrohelida, take yet to be placed in any supergroup. [10] [48]

Classification [ edit ]

Recent classification places the various amoeboid genera in the following groups:

| Supergroups | Major groups and genera | Morphology |

|---|---|---|

| Amoebozoa |

|

|

| Rhizaria |

| |

| Excavata |

|

|

| Heterokonta |

|

|

| Alveolata |

| |

| Opisthokonta |

|

|

| Ungrouped / unknown |

|

Some of the amoeboid groups cited (due east.chiliad., office of chrysophytes, role of xanthophytes, chlorarachniophytes) were non traditionally included in Sarcodina, beingness classified as algae or flagellated protozoa.

Pathogenic interactions with other organisms [ edit ]

Some amoebae can infect other organisms pathogenically, causing illness: [52] [53] [54] [55]

- Entamoeba histolytica is the cause of amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery.

- Naegleria fowleri (the "brain-eating amoeba") is a fresh-water-native species that can be fatal to humans if introduced through the nose.

- Acanthamoeba tin can cause amoebic keratitis and encephalitis in humans.

- Balamuthia mandrillaris is the cause of (often fatal) granulomatous amoebic meningoencephalitis.

Amoeba accept been found to harvest and grow the bacteria implicated in plague. [56] Amoebae can likewise play host to microscopic organisms that are pathogenic to people and aid in spreading such microbes. Bacterial pathogens (for example, Legionella ) tin can oppose absorption of food when devoured past amoebae. [57] The presently generally utilized and all-time-explored amoebae that host other organisms are Acanthamoeba castellanii and Dictyostelium discoideum. [58] Microorganisms that can overcome the defenses of 1-celled organisms can shelter and multiply inside them, where they are shielded from unfriendly outside conditions past their hosts.

Meiosis [ edit ]

Contempo bear witness indicates that several Amoebozoa lineages undergo meiosis.

Orthologs of genes employed in meiosis of sexual eukaryotes have recently been identified in the Acanthamoeba genome. These genes included Spo11, Mre11, Rad50, Rad51, Rad52, Mnd1, Dmc1, Msh and Mlh . [59] This finding suggests that the ''Acanthamoeba'' are capable of some class of meiosis and may exist able to undergo sexual reproduction.

The meiosis-specific recombinase, Dmc1, is required for efficient meiotic homologous recombination, and Dmc1 is expressed in Entamoeba histolytica . [threescore] The purified Dmc1 from E. histolytica forms presynaptic filaments and catalyses ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and Dna strand exchange over at least several thousand base pairs. [60] The Deoxyribonucleic acid pairing and strand exchange reactions are enhanced by the eukaryotic meiosis-specific recombination accessory factor (heterodimer) Hop2-Mnd1. [60] These processes are central to meiotic recombination, suggesting that E. histolytica undergoes meiosis. [60]

Studies of Entamoeba invadens found that, during the conversion from the tetraploid uninucleate trophozoite to the tetranucleate cyst, homologous recombination is enhanced. [61] Expression of genes with functions related to the major steps of meiotic recombination also increase during encystations. [61] These findings in East. invadens, combined with evidence from studies of E. histolytica indicate the presence of meiosis in the Entamoeba.

Dictyostelium discoideum in the supergroup Amoebozoa can undergo mating and sexual reproduction including meiosis when food is scarce. [62] [63]

Since the Amoebozoa diverged early from the eukaryotic family unit tree, these results suggest that meiosis was present early in eukaryotic development. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with the proposal of Lahr et al. [64] that the bulk of amoeboid lineages are anciently sexual.

References [ edit ]

- ^ "Amoeba" Archived 22 November 2015 at the Wayback Motorcar at Oxforddictionaries.com

- ^ Singleton, Paul (2006). Dictionary of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, 3rd Edition, revised . Chichester, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: John Wiley & Sons. pp.32. ISBN 978-0-470-03545-0 .

- ^ a b David J. Patterson. "Amoebae: Protists Which Motility and Feed Using Pseudopodia". Tree of Life spider web projection. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ "The Amoebae". The Academy of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009.

- ^ Wim van Egmond. "Sun animalcules and amoebas". Microscopy-United kingdom. Archived from the original on iv November 2005. Retrieved 23 October 2005.

- ^ Flor-Parra, Ignacio; Bernal, Manuel; Zhurinsky, Jacob; Daga, Rafael R. (17 Dec 2013). "Cell migration and division in amoeboid-like fission yeast". Biology Open. 3 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1242/bio.20136783. ISSN2046-6390. PMC 3892166 . PMID24357230.

- ^ Friedl, P.; Borgmann, S.; Bröcker, E. B. (1 October 2001). "Amoeboid leukocyte crawling through extracellular matrix: lessons from the Dictyostelium paradigm of cell movement". Periodical of Leukocyte Biology. lxx (iv): 491–509. ISSN0741-5400. PMID11590185.

- ^ a b Marée, Athanasius FM; Hogeweg, Paulien (2001). "How amoeboids self-organize into a fruiting trunk: multicellular coordination in Dictyostelium discoideum". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 98 (vii): 3879–3883. doi: x.1073/pnas.061535198 . PMC 31146 . PMID11274408.

- ^ Mackerras, M. J.; Ercole, Q. N. (1947). "Observations on the action of paludrine on malarial parasites". Transactions of the Regal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 41 (3): 365–376. doi:10.1016/s0035-9203(47)90133-8. PMID18898714.

- ^ a b c Jan Pawlowski: The twilight of Sarcodina: a molecular perspective on the polyphyletic origin of amoeboid protists. Protistology, Band v, 2008, S. 281–302. (pdf, 570 kB) Archived 14 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tan; et al. (2005). "A simple mass culture of the amoeba Chaos carolinense: revisit" (PDF). Protistology. four: 185–xc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ "Relationship with Humans". Amoeba proteus. 12 April 2013. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Alberts Eds.; et al. (2007). Molecular Biology of the Jail cell 5th Edition. New York: Garland Scientific discipline. p. 1037. ISBN 9780815341055 .

- ^ Margulis, Lynn (2009). Kingdoms and Domains . Academic Press. pp.206–seven. ISBN 978-0-12-373621-5 .

- ^ Ogden, C. One thousand. (1980). An Atlas of Freshwater Testate Amoeba. Oxford, London, and Glasgow: Oxford University Press, for British Museum (Natural History). pp. 1–five. ISBN 978-0198585022 .

- ^ Alberts Eds.; et al. (2007). Molecular Biology of the Cell 5th Edition. New York: Garland Science. p. 663. ISBN 9780815341055 .

- ^ Kudo, Richard Roksabro. "Protozoology." Protozoology quaternary Edit (1954). p. 83

- ^ Thorp, James H. (2001). Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates. San Diego: Academic. p. 71. ISBN0-12-690647-5.

- ^ Jeon, Kwang W. (1973). Biology of Amoeba . New York: Bookish Press. pp.100. ISBN 9780123848505 .

- ^ a b Mylnikov, Alexander P.; Weber, Felix; Jürgens, Klaus; Wylezich, Claudia (ane Baronial 2015). "Massisteria marina has a sister: Massisteria voersi sp. nov., a rare species isolated from coastal waters of the Baltic Sea". European Journal of Protistology. 51 (4): 299–310. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2015.05.002. ISSN1618-0429. PMID26163290.

- ^ "The Size, Shape, And Arrangement of Bacterial Cells". classes.midlandstech.edu. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 21 Baronial 2016.

- ^ a b Gooday, A. J.; Aranda da Silva, A.; Pawlowski, J. (1 Dec 2011). "Xenophyophores (Rhizaria, Foraminifera) from the Nazaré Canyon (Portuguese margin, NE Atlantic)". Deep-Sea Research Function Two: Topical Studies in Oceanography. The Geology, Geochemistry, and Biological science of Submarine Canyons Due west of Portugal. 58 (23–24): 2401–2419. Bibcode:2011DSRII..58.2401G. doi:x.1016/j.dsr2.2011.04.005.

- ^ "Encephalon-Eating Amoeba (Naegleria Fowleri): Causes and Symptoms". Archived from the original on 21 Baronial 2016. Retrieved 21 Baronial 2016.

- ^ "Anatomy Atlases: Atlas of Microscopic Anatomy: Department 4: Blood". www.anatomyatlases.org. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Acanthamoeba | Microworld". world wide web.arcella.nl. Archived from the original on eighteen August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Microscopy of Entamoeba histolytica". msu.edu. Archived from the original on v October 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Arcella vulgaris | Microworld". www.arcella.nl. Archived from the original on 18 Baronial 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Amoeba proteus | Microworld". world wide web.arcella.nl. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Chaos | Microworld". world wide web.arcella.nl. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Pelomyxa palustris | Microworld". www.arcella.nl. Archived from the original on eighteen Baronial 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ Friedl, Peter; Borgmann, Stefan; Eva-B, Bröcker (2001). "Amoeboid leukocyte itch through extracellular matrix: lessons from the Dictyostelium paradigm of cell movement". Journal of Leukocyte Biological science. seventy (4): 491–509. PMID11590185.

- ^ Nakagaki; et al. (2000). "Intelligence: Maze-solving by an amoeboid organism". Nature. 407 (6803): 470. Bibcode:2000Natur.407..470N. doi: ten.1038/35035159 . PMID11028990. S2CID205009141.

- ^ Wehr, John D. (2003). Freshwater Algae of Due north America . San Diego and London: Academic Press. pp.353. ISBN 978-0-12-741550-5 .

- ^ "Algae World: diatom sex and life cycles". Algae Globe. Imperial Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Valle, L.Thou. (2014). "New species of Paramoebidium (trichomycetes, Mesomycetozoea) from the Mediterranean, with comments about the amoeboid cells in Amoebidiales". Mycologia. 106 (3): 481–90. doi:10.3852/13-153. PMID24895422. S2CID3383757.

- ^ Taylor, J. W. & Berbee, Grand. L. (2014). Fungi from PCR to Genomics: The Spreading Revolution in Evolutionary Biology. In: Systematics and Development. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 52, [1] Archived 30 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Corliss, J. O. (1987). "Protistan phylogeny and eukaryogenesis". International Review of Cytology. 100: 319–370. doi:x.1016/S0074-7696(08)61703-9. ISBN 9780080586373 . PMID3549607.

- ^ Rosenhof, R. (1755). Monatlich herausgegebene Insektenbelustigungen, vol. three, p. 621, [two] Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jeon, Kwang W. (1973). Biological science of Amoeba . New York: Academic Press. pp. two–3, [3]. ISBN 9780123848505 .

- ^ McAlpine, Daniel (1881). Biological atlas: a guide to the practical study of plants and animals . Edinburgh and London: W. & A. K. Johnston. pp.17.

- ^ Bory de Saint-Vincent, J. B. G. M. "Essai d'une nomenclature des animaux microscopiques." Agasse, Paris (1826).p. 28

- ^ McGrath, Kimberley; Blachford, Stacey, eds. (2001). Gale Encyclopedia of Scientific discipline Vol. 1: Aardvark-Goad (2nd ed.). Gale Group. ISBN 978-0-7876-4370-6 . OCLC46337140.

- ^ Ehrenberg, Christian Gottfried. Organisation, systematik und geographisches verhältniss der infusionsthierchen: Zwei vorträge, in der Akademie der wissenschaften zu Berlin gehalten in den jahren 1828 und 1830. Druckerei der Königlichen akademie der wissenschaften, 1832. p. 59

- ^ Dujardin, Felix (1841). Histoire Naturelle des Zoophytes Infusoires . Paris: Librarie Encyclopedique de Roret. pp.26.

- ^ Schmarda, Ludwig Karl (1871). Zoologie . Due west. Braumüller. pp.156.

- ^ Bütschli, Otto (1882). Klassen und Ordnungen des Thier-Reichs I. Abteilung: Sarkodina und Sporozoa. Paleontologische Entwicklung der Rhisopoda von C. Scwager. p. 1.

- ^ Calkins, Gary N. (1909). Protozoölogy . New York: Lea & Febiger. pp.38–twoscore.

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; et al. (2012). "The Revised Nomenclature of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 59 (5): 429–93. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. PMC 3483872 . PMID23020233.

- ^ a b Park, J. S.; Simpson, A. G. B.; Brown, Due south.; Cho, B. C. (2009). "Ultrastructure and Molecular Phylogeny of 2 Heterolobosean Amoebae, Euplaesiobystra hypersalinica gen. Et sp. Nov. And Tulamoeba peronaphora gen. Et sp. November., Isolated from an Extremely Hypersaline Habitat". Protist. 160 (2): 265–283. doi:ten.1016/j.protis.2008.10.002. PMID19121603.

- ^ Ott, Donald W., Carla K. Oldham-Ott, Nataliya Rybalka, and Thomas Friedl. 2015. Xanthophyte, Eustigmatophyte, and Raphidophyte Algae. In: Wehr, J.D., Sheath, R.G., Kociolek, J.P. (Eds.) Freshwater Algae of North America: Ecology and Classification, second edition. Bookish Press, Amsterdam, pp. 483–534, [4] Archived 22 Jan 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Patterson, D. J.; Simpson, A. Chiliad. B.; Rogerson, A. (2000). "Amoebae of uncertain affinities". In: Lee, J. J.; Leedale, K. F.; Bradbury, P. An Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa, 2d ed., Vol. 2, p. 804-827. Lawrence, Kansas: Society of Protozoologists/Allen Press. [5] Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Genera considered ungrouped/unknown past this source in 2000 but which have since get classified take been moved to those classifications on Wikipedia.

- ^ Casadevall A (2008) Development of intracellular pathogens. Annu Rev Microbiol 62: nineteen–33. ten.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093305 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ^ Guimaraes AJ, Gomes KX, Cortines JR, Peralta JM, Peralta RHS (2016) Acanthamoeba spp. as a universal host for pathogenic microorganisms: One bridge from environs to host virulence. Microbiological Enquiry 193: 30–38. 10.1016/j.micres.2016.08.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ^ Hilbi H, Weber SS, Ragaz C, Nyfeler Y, Urwyler S (2007) Environmental predators as models for bacterial pathogenesis. Environmental microbiology nine: 563–575. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01238.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ^ Greub, G; Raoult, D (2004). "Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 17 (ii): 413–433. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.2.413-433.2004 . PMC 387402 . PMID15084508.

- ^ "Are amoebae safe harbors for plague? New enquiry shows that plague bacteria not simply survive, but thrive and replicate one time ingested by an amoeba".

- ^ Vidyasagar, Aparna (April 2016). "What Is an Amoeba?". livescience.com . Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Thewes, Sascha; Soldati, Thierry; Eichinger, Ludwig (2022). "Editorial: Amoebae as Host Models to Written report the Interaction with Pathogens". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. nine: 47. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.00047 . PMC 6433779 . PMID30941316.

- ^ Khan NA, Siddiqui R (2015). "Is there evidence of sexual reproduction (meiosis) in Acanthamoeba?". Pathog Glob Health. 109 (four): 193–5. doi:10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000009. PMC 4530557 . PMID25800982.

- ^ a b c d Kelso AA, Say AF, Sharma D, Ledford LL, Turchick A, Saski CA, King AV, Attaway CC, Temesvari LA, Sehorn MG (2015). "Entamoeba histolytica Dmc1 Catalyzes Homologous DNA Pairing and Strand Exchange That Is Stimulated past Calcium and Hop2-Mnd1". PLOS One. 10 (nine): e0139399. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1039399K. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139399 . PMC 4589404 . PMID26422142.

- ^ a b Singh N, Bhattacharya A, Bhattacharya Due south (2013). "Homologous recombination occurs in Entamoeba and is enhanced during growth stress and stage conversion". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e74465. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...874465S. doi: x.1371/periodical.pone.0074465 . PMC 3787063 . PMID24098652.

- ^ Flowers JM, Li SI, Stathos A, Saxer G, Ostrowski EA, Queller DC, Strassmann JE, Purugganan MD (2010). "Variation, sexual activity, and social cooperation: molecular population genetics of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum". PLOS Genet. 6 (7): e1001013. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001013. PMC 2895654 . PMID20617172.

- ^ O'24-hour interval DH, Keszei A (2012). "Signalling and sex in the social amoebozoans". Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 87 (2): 313–29. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00200.x. PMID21929567. S2CID205599638.

- ^ Lahr DJ, Parfrey LW, Mitchell EA, Katz LA, Lara E (2011). "The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex activity in amoeboid organisms". Proc. Biol. Sci. 278 (1715): 2081–90. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0289. PMC 3107637 . PMID21429931.

Further reading [ edit ]

- Walochnik, J. & Aspöck, H. (2007). Amöben: Paradebeispiele für Probleme der Phylogenetik, Klassifikation und Nomenklatur. Denisia 20: 323–350. (In German)

- Amoebae: Protists Which Move and Feed Using Pseudopodia at the Tree of Life web project

- Pawlowski, J. & Burki, F. (2009). Untangling the Phylogeny of Amoeboid Protists. Periodical of Eukaryotic Microbiology 56.ane: sixteen–25.

External links [ edit ]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amoeba . |

- Siemensma, F. Microworld: world of amoeboid organisms.

- Völcker, Due east. & Clauß, Southward. Visual primal to amoeboid morphotypes. Penard Labs.

- The Amoebae website of Maciver Lab of the Academy of Edinburgh, brings together data from published sources.

- Molecular Expressions Digital Video Gallery: Pond Life – Amoeba (Protozoa) – informative amoeba videos

Are Amoeba Plant Like or Animal Like

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amoeba

Comments

Post a Comment